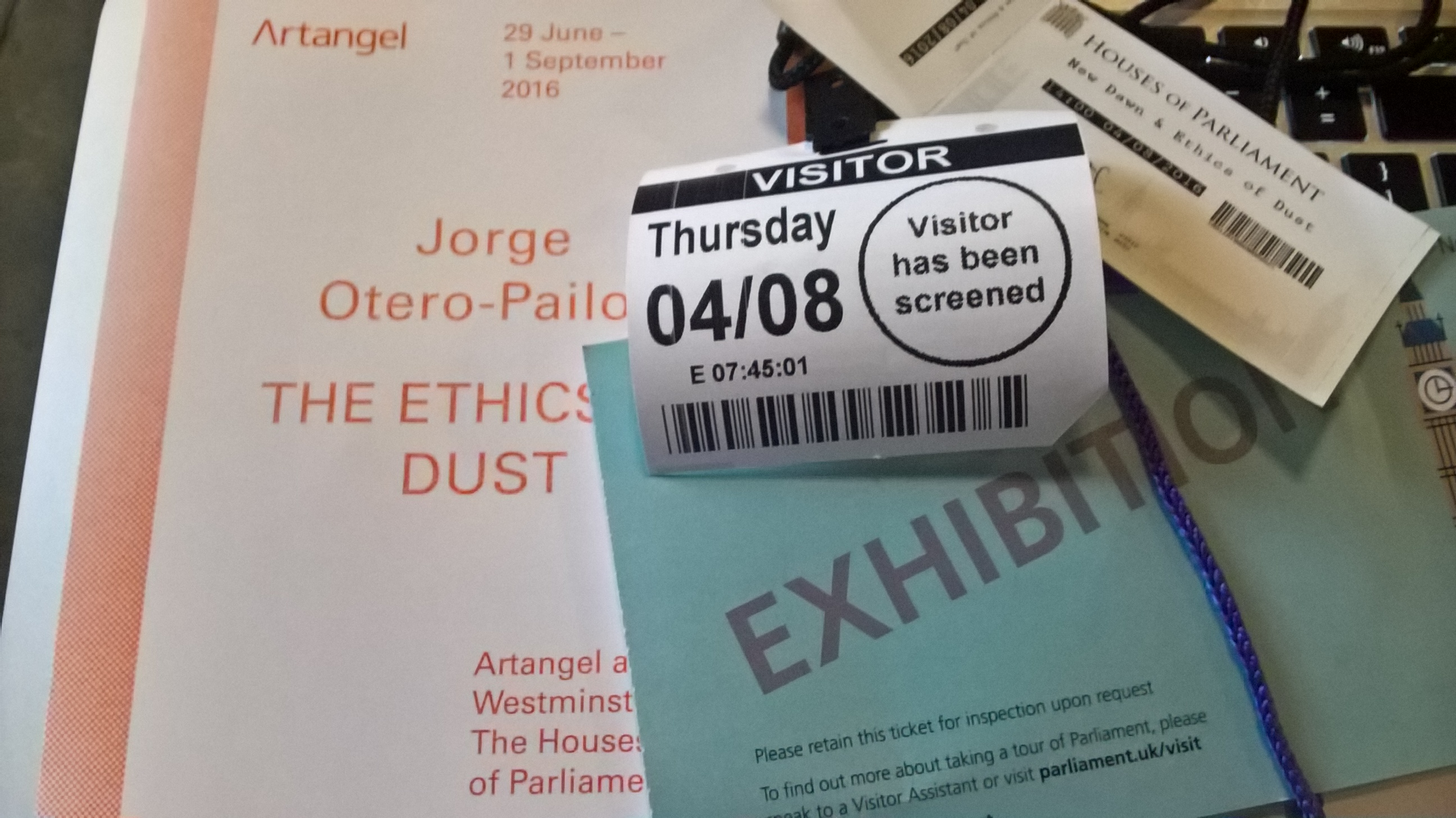

The Ethics of Dust

This month (August 2016) I visited Westminster Hall at the Palace of Westminster (a UNESCO world heritage site) to see The Ethics of Dust. Commissioned and produced by Artangel, this exhibition by artist Jorge Otero-Pailos consists of a 50-meter long and 6–meter high latex cast of the east wall, generated from a restoration to remove surface pollution. By spraying and then gently peeling off latex, Otero-Pailos has given the Hall a facial. And, like all good facials, it has renewed through a thorough cleanse by lifting over 900 years of accumulated dirt, dust, soot, and grime from the limestone wall. The resulting cast, embedded with this dirt and gently glowing from natural- and spot-lighting, hangs suspended from the roof adjacent to the east wall.

By spraying and then gently peeling off latex, Otero-Pailos has given the Hall a facial. And, like all good facials, it has renewed through a thorough cleanse by lifting over 900 years of accumulated dirt, dust, soot, and grime from the limestone wall.

The Ethics of Dust suggests an interplay between permanence-impermanence, absence-presence, and the solid-fragile. These are qualities that could be said to characterise many heritage sites, but are made especially visible through Otero-Pailos’s site-based intervention of this dusty imprint. The cast at times appears solid. Yet this perception is unsettled as it sways gently in a breeze from the Hall entrance, and a distinct latex smell reminds the viewer that this is not stone but a far more delicate and ephemeral substance. The tea-stained colour, and folds and creases in the cast, evoke aged paper. Like a hanging map, I find myself attempting to ‘read’ the cast trying to spot identifying features to match it to the original wall as I walk its length. In doing so, and perhaps taking on the focused vision of those tasked with this preservation project, small details otherwise overlooked emerge: a hairline crack here, a dent there, a different sized limestone block. Simultaneously it evokes shed skins, or shrouds used to wrap and encase. Such analogies – of emergence, protection, and way-finding – are especially apt for an artwork which, essentially, is the by- or waste-product of a conservation process used to ensure the future longevity of this heritage site.

Recent examples of digital scanning and 3D printing used in preservation to recreate heritage sites also come to mind when viewing The Ethics of Dust. For example, the replica of the Triumphant Arch from Palmyra (Syria) destroyed by Isis in October 2015, and reconstructed and installed in London’s Trafalgar Square earlier this year. Yet Otero-Pailos’s cast is not intended to be an exact replica or a reconstruction but is something very different. By lifting layers of embedded dust from the original wall, I find myself thinking of the palimpsest as the work removes and displays these layers as tangible traces of past events and times (a metaphor our Heritage Futures researcher Nadia Bartolini has explored in other contexts). By putting the practices and processes of conservation on display, the dust is positioned to be both a substance considered to pose a threat to the future durability of this heritage site, and yet is also re-positioned as heritage in itself. The accompanying catalogue presents the dust as a witness to past events, if not indeed actually produced by and evidence of these events: ‘Westminster Hall dates back to 1099 and its limestone walls have held the dust, soot and dirt from events including the Great Smog of 1952 and the trials of Guy Fawkes in 1606 and King Charles I in 1649’ we are told. This ephemeral substance is exhibited as holding historic value, and (it is implied) by fixing the dust in latex traces of past events are made all the more tangible.

By conceptualising dust as both destructive (pollutant) and constitutive (palimpsest trace) of heritage, I suggest that the intervention also foregrounds the reluctance to ‘let go’ in the realm of cultural heritage driven by a preference for ‘loss aversion’ (Holtorf 2015). The dirt has been successfully removed. Yet it has not been discarded but exhibited as substance with historical value. A substance that, once removed from the stone, is unlikely in contemporary post-Clean Air Act (1956) Britain to return (or at least to the extent of past blackened industrial British cities). Drawing links to the Profusion theme on which I research, this cast reminds me of the traces of objects ‘let go’ in the museum context. Our research on processes of review and rationalisation show how letting go of things sometimes creates new kinds of profusion – for example, information and documentation. Catalogue records for objects that are disposed or dispersed from collections are updated with information to document these decisions, record motivations, and evidence that appropriate processes were followed and due diligence taken. The dusty cast, like such catalogue records, may be viewed as a remnant or trace of specific heritage decisions and negotiations. A remnant that is retained and held onto, partly perhaps, as a performance of care.

On entering the exhibition a security guard screening my bag rather dryly announced that I was ‘just going to see some dusty old sheets’. Dusty old sheets these may be. Yet sheets (as I hope this dispatch has shown) that I have found beautiful, intriguing, and ultimately provocative for the questions they raise about the processes and practices of cultural heritage.

Dusty old sheets these may be. Yet sheets that I have found beautiful, intriguing, and ultimately provocative for the questions they raise about the processes and practices of cultural heritage.