On filing

Borges imagines a Total Library, put together perhaps by Huxley’s typing pool of monkeys, given enough time (but one immortal monkey will do, notes Borges). He calls it a subaltern horror: the vast, contradictory Library whose vertical wildernesses of books run the incessant risk of changing into others that affirm, deny, and confuse everything like a delirious god. The space it would take up!

Conserving diversity seems a little like this sometimes. The 50 to 500 seeds per little foil packet that comprise each of the 855,000 seed varieties held in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, the 2.2 million varieties held worldwide; the hundreds of DNA samples held by the Frozen Ark; the 400 or so languages in the Endangered Languages Archive. The vastness of the specifics of diversity.

There is a filing cabinet in Rodney’s office. I’ve never noticed it before. I’ve seen it, of course, but never really seen it. All rooms have filing cabinets. Does anyone use them anymore? But suddenly it appears when we talk about archiving practices one day. Rodney jokes that he only opens it to hide whatever pile of papers he doesn’t know what to do with. Those of us in the room that have filed for a living have a moment of nostalgia. I remember the satisfaction of flicking at speed through the alphabetized crystal file tabs and dropping ordered annotated sheets of paper into the green hanging files. Standardized A4 sheets and green hanging files: techniques of ordering the world, the machinery of archives. Globe-Wernicke began producing its patented vertical filing cabinets at the end of the 19th century: the beginning of smooth standardized draws and file sizes (so many standards!) that must fill whole quarries somewhere, redundant and rotten or rusty. And what of the humble filing clerk? Her (or his) agency in those techniques of ordering was integral to the archive. In effect they were the archivists of bureaucracy; of management and information flow. Record. The files keep the records.

Sven Spieker writes in The Big Archive: art from bureaucracy, that “[a]rchives contain paperwork that no longer circulates in the bureaucracy, paperwork that has lapsed and become garbage.” Paperwork that has been filed. But we can always go back to check. The actuality, the materiality of what was said or what was stored, and that is what is. Vismann argued that the archives – the material in and of the files – were vital to the emergence of statecraft: the Roman Empire legitimated itself through recourse to its files: “a form of state-sponsored politics with the past, an official instruction to forget or remember.” No longer being in circulation isn’t an end point at all. Indeed, the filing clerks and the archivists have made selections, crafted through inclusion and exclusion. Is the archivist a storyteller? Ask Duff and Harris. They are “members of a big family of record makers” and they have created the architecture and the descriptive architecture with which records are made. They “will remember certain aspects and hide or forget others.”

The technologies of record-keeping of the late 19th and early 20th century – typewriters, duplicating machines, filing systems – created volumes of material records hitherto unknown. The impossibility and the horror of the immortal monkey’s task might have looked close, necessitating more technologies. But the record is always distorted, even if it is only through the elusive nature of the incomplete. How should we represent that which we choose to ignore? Where are the holes in the stories? By standardizing – through green hanging files, or international protocols – how do we allow for the heterogenous – the eccentric, the individual, the bland, the hybrid – in the smooth technologies? Deconstructing the organising processes and classification systems is an ongoing project, but some standards and systems are open to deconstruction: the records that are always being made, the filing that the clerks were always doing. The ongoing and the unfinished into and out of the future. The life in the archive, the life of the architectures.

Is the archivist a storyteller? Ask Duff and Harris. They are “members of a big family of record makers” and they have created the architecture and the descriptive architecture with which records are made.

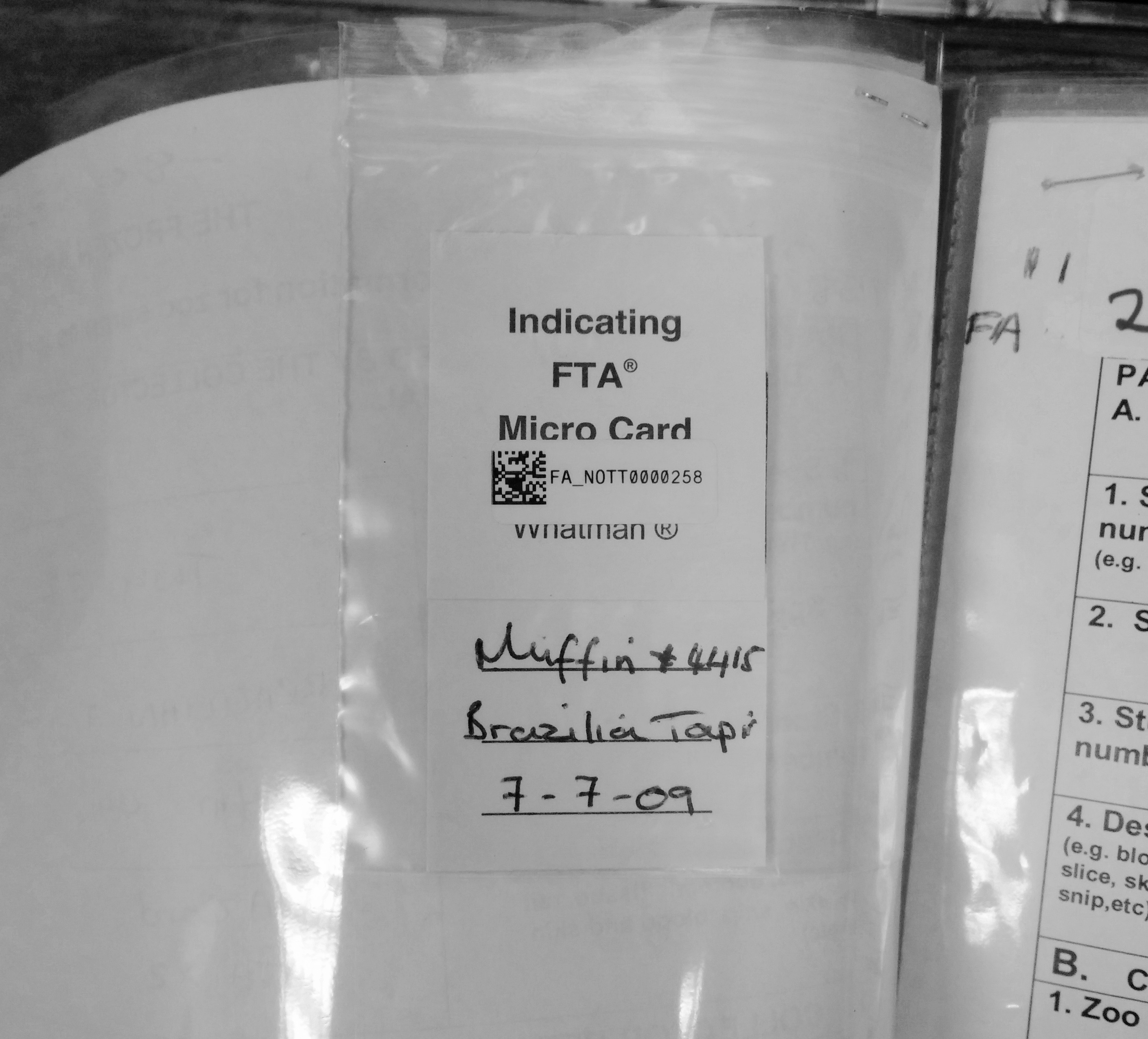

However, conserving diversity is a task that takes place against the clock. That’s the heroic work: the fieldworker noting the dying language, the genebanks isolating their phenotypes, the swabbing of the beasts for their DNA samples. Then the clerks pack the boxes, enter the metadata into the digital records. Duff and Harris argue for “cross-box and multiple box positioning,” and perhaps this is where it happens. The stories that the files tell: Borges’s Library of Babel was decoded on identifying the Samoyedic Lithuanian dialect of Guarani of one of the books, that although all books shared common form, they were all different. In the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, the Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea uses well-made wooden boxes; Canada’s are cardboard; ICARDA’s grey stacking plastic. The selection criteria for the vessels are a hole in the archive. The Crop Trust’s web image for the vault shows identical black boxes, but the genebanks that deposit in the vault are only given dimension criteria. They may choose their own boxes. In the Frozen Ark, the little card that holds the DNA swab of the Brazilian tapir gives its name, Muffin. Through the portal to the Endangered Languages Archive (ELAR), you can search all the languages that are open. I type in “magic”: there are 24 records. I click the first: a story about a prince who has the form of a fish. He marries a woman, who on the wedding night is given some magic pills that she can use to transform the fish into the form of a man.

The magic’s in the metadata.

References:

Borges, Jorge Luis, 1999. The Total Library, in The Total Library: Non-Fiction 1922-1986. Penguin.

Borges, Jorge Luis, 1985. The Library of Babel, in Fictions. Calder Publications.

Duff, Wendy M. and Verne Harris, 2002. Stories and Names: Archival Description as Narrating Records and Constructing Meanings. Archival Science 2: 263-285.

Spieker, Sven, 2008. The Big Archive: art from bureaucracy. MIT Press.

Vissman, Cornelia, 2008. Files: Law and Media Technology. Stanford University Press.

I type in “magic” into the Endangered Languages Archive (ELAR) portal: there are 24 records. I click the first: a story about a prince who has the form of a fish. He marries a woman, who on the wedding night is given some magic pills that she can use to transform the fish into the form of a man.